Robots can improve the flow of blood donations

The Swinburne team has designed a robot arm to automate the blood donation pack folding process. The arm holds the folded blood pack, which is filled with water, to demonstrate that this process can be automated.

In summary

- Swinburne researchers have proved that automation of the essential 'folding' process for blood donation packs is possible

- Automation will reduce staff injuries and human error

- The IMCRC-funded project has been extended to see if the robot can fold faster

Blood processing is largely manual.

At a processing centre, whole blood donations must be separated into its cellular components via centrifugation. To do this, the blood pack must be folded in a particular way to ensure during the process there is no bacterial contamination (which, in turn, increases shelf life).

Staff are highly trained to carry out this operation, but there are still risks and instances of human error. Damaged or torn packs not only lead to the loss of a precious donation, but also disrupt production and expose staff to potentially hazardous biological materials. Even subtle non-conformities can occur and build over time, leading to quality deviations. On the other hand, such repetitive motions – sometimes hundreds a day – can cause ergonomic strain and injury for staff.

Staff demonstrate the repetitive folding process, which can lead to both injury and human error. This process is then completed by a robot arm, vision system and more.

Can a robot do the job?

Swinburne researchers have worked to automate the folding and centrifuge-tube loading process using collaborative robotics, vision systems, jigs and actuators.

Folding is a highly complex procedure that is challenging to automate using robots. The blood packs are soft and "deformable" objects, which can lead to a significant variation in shape and geometry. This makes it difficult for a robot or computer that is not suited to the myriad of geometries.

In fact, the automation of the manipulation of soft deformable objects is a hot topic in robotics research. That’s why IMCRC was so keen to fund the project. As well as the practical, impactful social good that success could have in the blood donation space, it could be a step forward for automation and innovative manufacturing.

The Swinburne team has been looking for any automation opportunities in the process –breaking it down into smaller steps and building in design and engineering contingencies so that the final design could involve a combination of semi-automated, automated or assisted processes.

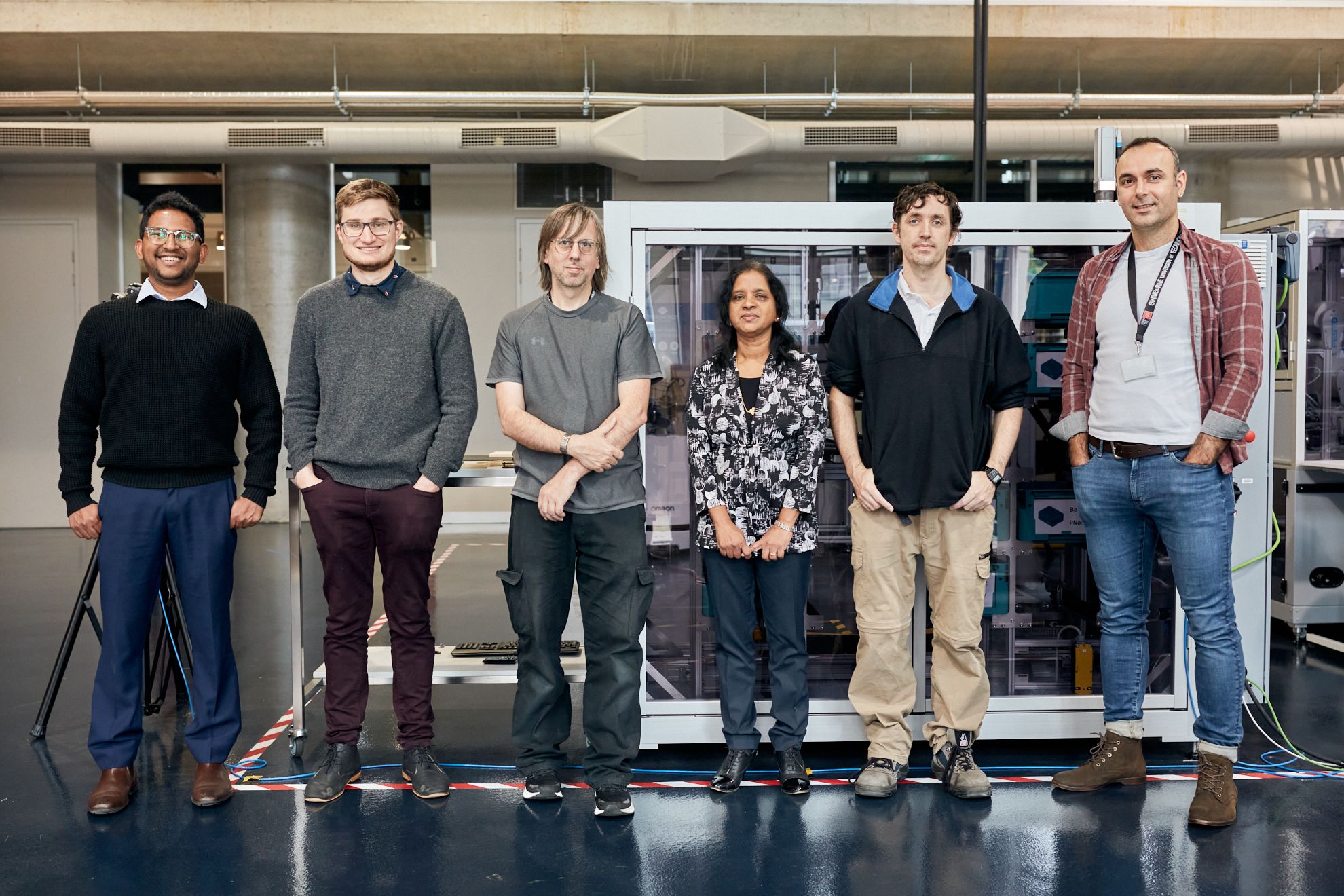

The Swinburne research team, from left to right: Ashen Vihana, Andrew Howarth, Craig Webster, Shanti Krishnan, David Smoors and Hasan Baran Kaptan.

The nuts and bolts of automation

Within three months, the team knew they could not only automate the process – but also add to the project scope.

They built a proof-of-concept robot arm that shows automation can be used to fold whole blood collection packs. But they also built in image recognition for quality inspection, data recording for traceability, anomaly detection in manually placed stickers/labels and more.

Project lead and Deputy Director of Swinburne’s Factory of the Future, Dr Shanti Krishnan, says, “I was very excited at the challenge of finding an automated innovative solution to the problem of a repetitive manual process in the medical industry, using collaborative robots and machine vision systems.

“I am proud to say that the dedicated team effort of engineering excellence and applied research at Swinburne’s Factory of the Future has resulted in the successful completion of the proof of concept design.”

The project has also been extended with a new aim: to make the robot faster. Since it’s currently much slower than a human, speed will be a crucial step to integrating this safer, more accurate process.

For the Swinburne team, the success in this project has broader ramifications.

“The findings could also be translated to other, similar processes involving soft deformable objects – with an impact on food, health, agriculture and other industries. Basically, anything dealing with packaging.”

-

Media Enquiries

Related articles

-

- Technology

New research finds Instagram promotes white appearances, cultural appropriation and plastic surgery via filters

New research finds Instagram filters promote white beauty standards, selective cultural appropriation and allow users to ‘try on’ risky surgical procedures.

Thursday 24 July 2025 -

- Health

Can oranges, garlic and echinacea really help avoid the cold and flu?

Swinburne Dietetics Lecturer Dr Nina Imad shares how to help avoid the cold and flu.

Thursday 10 July 2025 -

- Technology

- Science

- University

- Engineering

Swinburne to advance battery life and EV cybersecurity with Australian Research Council grants

Swinburne has secured two grants from Australian Research Councils to advance research in energy storage and cybersecurity.

Wednesday 02 July 2025 -

- Technology

- Science

- University

- Sustainability

Swinburne powers breakthroughs in sustainable mining and materials technology

Swinburne innovators have been awarded $4 million in funding from the Australian Government, driving Australia’s future in sustainable innovation through two groundbreaking projects.

Tuesday 15 July 2025 -

- Technology

Microsoft, IBM and Google are racing to develop the first useful quantum computer. Ultracold neutral atoms could be the key.

Swinburne University of Technology has been exploring ultracold neutral atoms for two decades.

Monday 30 June 2025