Factory of the Future’s innovative take on digital twins

In Summary

- Twin technology has provided researchers with duplicates of real engineering systems since the 1960s

- It become increasingly accessible thanks to rapid technological advancements

- Researchers at Swinburne’s Factory of the Future have flipped the usual development of digital twin technologies, creating a virtual copy of a robotic work station before the physical entity

Imagine designing an innovative, new technology and being able to monitor its progress, without even physically creating it yet.

Researchers at Swinburne’s Factory of the Future are doing just that. They are developing a virtual copy of a robotic work station to simulate its functioning and understand how it operates, before building commences.

This virtual copy is a digital twin – an exact replica of a physical entity that researchers can use to assess a system’s current and future capabilities during its lifecycle, among other purposes.

Swinburne’s novel approach is flipping the usual development of digital twin technologies, by designing the digital duplicate first, rather than using it to analyse an established physical system.

To understand this progress, we can look back on the origins and evolution of this technology.

Reality to virtuality

Twin technology, the initial creation of duplicated systems, was used in NASA’s Apollo missions so engineers could resolve problems with the same technology astronauts used in space.

But a physical copy would eventually be digitalised by industry advancement.

The term ‘digital twin’ was devised by Dr Michael Grieves at the University of Michigan, in a paper published in 2002.

Dr Grieves said these virtual copies “would be a ’twin‘ of the information that was embedded within the physical system itself” and allow researchers to detect and monitor previously unpredictable or undesirable problems that would otherwise go unnoticed.

Today, the digital age has transformed these mirrored systems to be wirelessly accessible, convenient and applicable to numerous industries in real-time, such as healthcare, space, infrastructure and manufacturing.

Widespread Web

The Internet of Things (IoT) improved the accessibility of digital twin technology.

Aside from digital twins, this network of devices includes artificial intelligence, augmented reality, cybersecurity systems and cloud computing software.

The IoT is a key part of the fourth industrial revolution, Industry 4.0, which is the advancement of automation technology and data exchange to enhance products and machines in the physical world.

The sensors involved with digital twin technology process information at a rapid rate, providing real-time results about the physical system they are connected to.

Digital twins can:

- Imitate processes of physical systems

- Discover what a system lacks by simulating results

- Improve future manufacturing methods

- Refine designs and models through data

Swinburne’s impact

By 2020, the International Data Corporation estimates 30 per cent of the top 2,000 global companies will be using digital twin technology to enhance product innovation and efficiency.

Swinburne’s own Social Innovation Research Institute (SIRI) is exploring the societal implications of living with and adapting to the digital economy as part of its Society 4.0 initiative. And, it is the constant pursuit of automated technology that places digital twins at the forefront of innovation.

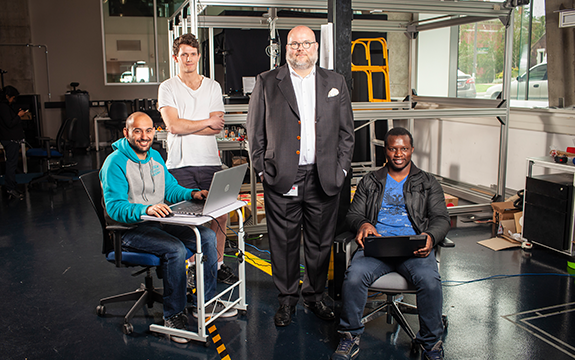

Director of Factory of the Future, Associate Professor Nico Adams, says the technology will greatly reduce the risks involved in physical production.

“The virtual commissioning that we are doing now will significantly help with the eventual production of the robotic work station. We are using a digital twin as design inspiration, or a blueprint if you will, to assess how the system will run over time before we build it,” he says.

“By doing so, we will be able to notice any defects or problems that may arise in normal functioning and change the design to resolve that.”

Future Focus

At the Factory of the Future, Swinburne’s hub of research and innovation, digital twins will be used by partner companies across a range of software that can simulate product lifecycles.

This will enable digital twin technology to support design, visualisation and testing in a virtual environment.

Professor Adams says that while digital twins are a growing area of research and development, it will still take decades of improvement to bring the concept to a commercial level.

“Digital twins are still quite a new concept, and a very expensive one at that, so it will take time to develop the technology on many levels,” he says.

“It also depends on what kind of digital twin is being created. Even designing a twin for a 3D printer can involve researchers from different disciplines, experimental models and years of refining the technology.”

“Creating cost-effective, detailed digital twins of larger infrastructure will certainly have to wait until current technology is able to take on the task – right now it is still a significant engineering effort.”